Waiting for the (Thin) Man (David Bowie)

by Todd Simmons The Brooklyn Rail, New York.

Somewhere off I-5 in the woods south of Portlandia, James Angell, Oregon’s wizard of psychedelic pop, is probably tinkering in his home studio and thinking, “It’s still your move, David Bowie.” After all, Angell was minding his own business in 2004, eating breakfast with his wife and daughter, when a call came in from New York. He never asked for it. He was living amongst the Portland civilians, quietly creating original music and working for a living, trying to forget about the dying commercial music industry. Just as Bob Pollard taught school in Ohio on breaks from Guided by Voices and Mark Ibold tended bar in NoHo between the end of Pavement and his new gig with Sonic Youth. Just like those guys, James Angell couldn’t sit around waiting for the biz to get it. He built stuff for a living, to feed his family. He built his own house. In which he built a studio. Where he sat with his eggs when his wife Erin answered the phone. “James,” she said, “it’s…uh…David Bowie on the line.”

The Thin White Duke had gotten his paws on one of Angell’s albums in NYC and “loved it,” according to mutual friend Courtney Taylor-Taylor (former drummer for Angell’s defunct psych-rock outfit, Nero’s Rome). Living near the NYC studio where Taylor-Taylor’s band the Dandy Warhols was working, Bowie popped round for a mug of tea to check out what the younger musicians were into. Bowie was cool like that. He had lived in NYC for years and was notorious for dropping in at local clubs, keeping up with the burgeoning scene afoot in Brooklyn. He’d released two well received albums in the ’00s and was touring incessantly. Bowie said that he was seeking unsigned talent for a new label, so the Portland Dandy did his old friend a favor and handed him Angell’s hypnotic first solo album, Private Player. Impressed, Bowie quickly tracked Angell down. Skeptical that James wasn’t already committed to a label at that time, he nevertheless got his number from Taylor-Taylor and dialed the cabin outside of Stumptown.

Angell took the receiver. “Hello?” The cheerfully refined cockney voice on the other end introduced himself: “James, this is David Bowie. Is this a good time?” Incredulous, Angell gazed out the window into some pine trees as the former Ziggy Stardust described how very much he’d enjoyed listening to Private Player. “This is the sort of music I would hope to make myself,” Bowie explained, as Angell tried to keep the earth from swallowing him up. “He’s actually pitching me,” Angell realized with amazement.

Following the demise of two major-label deals in the ’90s for Nero’s Rome, Angell and guitarist Tod Morrisey went their separate ways. For Angell, that meant getting back to the woods to build a house, and to his first love, the piano. Angell was home-schooled by his Baptist minister father, and he learned to sing and play piano in church as a child. His first influence was Bach, and he wasn’t exposed to rock until much later. As traces of pop music started to penetrate the pious filter—mostly from passing cars and movie soundtracks—strange seeds were planted in his young imagination. He started a rock band that was “too difficult” to categorize by industry standards, and they were washed away in a wave of grunge hysteria, unable to find a niche. Weary of bands, smoky vans, and fast-talking suits, Angell retreated to his cabin to create Private Player. And then Bowie called.

He was packed for a European tour, and hoped that James might refrain from signing a deal anywhere before they could sit down and come to an “arrangement.” Angell was thrilled that somebody who knew something about good music was interested in his. He quickly decided that even if the industry knuckleheads who had yet to come around to him did so tomorrow, he would politely tell them to…uh…scram. He’d happily await the end of Bowie’s “A Reality Tour.” Who better to shepherd his dreamy orchestral pop music than this chameleonic (and influential) figure? Things were certainly looking up since they’d scrambled those eggs for breakfast.

And then fate stepped in. Bowie’s tour ended abruptly when he suffered a massive coronary that brought all his activities to a full stop. He would need to have major heart surgery and scrap all plans—including the post-it note he stuck on his SoHo fridge below Iman’s pilates schedule that said: Call James Angell back (or so we might imagine). All future recording plans were cancelled. The undertaking of starting a new record label would have to wait. Bowie’s heart was ailing, his life was at risk, and the ride was over for now—so much so that Rolling Stone, nearly 10 years later, asked in a cover story: “Where is Bowie?”

Years after that fateful tour, following a performance with the Loser’s Lounge at Joe’s Pub, I was speaking to musician Joe Hurley when the subject of Bowie came up. Hurley told me that he’d worked with Bowie associate Tony Visconti, and Visconti had told him that Bowie was in more serious shape than had been revealed in the press. “We may have seen the last of Bowie as a public figure, according to Tony,” Hurley sighed. “And he should know.” So it was confirmed by Bowie’s longtime producer: He had gone into hiding to recuperate. And subsequently, aside from a few random guest gigs, the man has gone from public workaholic to private Garbo.

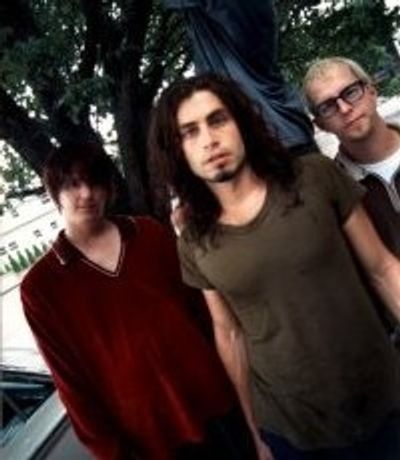

And where did all this leave James Angell? With two magnificent solo records under his belt and countless musicians from a flourishing Portland scene willing to tour if he could just garner the necessary financial support. A decade after the surprise phone call, Angell is still in Portland, building things, well accustomed to making things happen on his own. Both Private Player and last year’s self-released The Pandemic Symphony can be found on Amazon and iTunes. Angell has not toured per se, but has played to audiences on both coasts and appeared on various radio shows. One of these live performances caught the attention of Duran Duran’s John Taylor, who was a bona fide fan of Private Player. In late 2002, he attended Angell’s solo gig at the now-defunct East Village cabaret Fez. This encounter led to a showcase concert at Portland’s Avalon Theatre in 2003, involving some of Angell’s longtime collaborators and the pop superstar on bass. A live DVD of the event, Private Player in Concert, was released in 2004, revealing the intricate power of Angell’s piano-heavy songs when fleshed out with a full band. That night at the Avalon, Daniel Riddle’s spacey ringing guitar lines and Kevin Cozad’s synth and vocal harmonies reproduced the atmospherics that are always so potent on record. A rhythm section consisting of drummer/producer Tony Lash of Heatmiser and Taylor on bass added the propulsive pacing and thrust that Angell’s piano and vocals rode throughout the tight set. With Angell’s highly charged performance and the audience’s fervent reaction the show looks like a career-defining moment, but no major record deal would follow from it. It would, however, give Angell much-needed momentum going into the creation of his current album, The Pandemic Symphony.

The self-released, ambitious new record’s opener, “I Followed Myself to NYC,” is a scorching post-9/11 track that peels out of the gate and races to a finish, climaxing with an angelic chorus of voices. It is one of several tracks that are faster than anything Angell’s done previously, and establishes early on that this record is more ambitious and larger in scale than Private Player. The song captures the bizarre horror of that day: “A hole in the ground the size of the moon” is what Angell finds in New York after flying in from Oregon to find his “long-lost brother” in the aftermath. “Somebody’s gonna swing for it—burn in Hell forever.” Sidestepping the obvious tragedy of the terrible day, he calls out the facts like a street-corner philosopher, in a disturbingly playful, sing-song cadence, “If you ain’t afraid to commit suicide—if you ain’t afraid to let go of it and die—you can do anything you wanna do.”

Angell’s lyrics are both tender and toxic; they could be semi-autobiographical or pulled from newspaper headlines. Topics range from a frozen Iceman to 9/11 and beyond. The pleas of the nearly perfect “Hiding in Plain Sight” convey an artist’s anguish as he implores his wife to keep her faith in him after years of a struggle leading from optimism to despair (“I know I’ve been so angry—it’s so hard to wait”) and back.

“The Horse No One Can Ride” is a drug-user’s fantasy revenge plot against an exploitative dealer. Tightly wound, explosive rhythms gallop along, replete with whip-cracks and Riddle’s tremolo guitar, manifesting as a sleazy thriller about a man’s attempt to wrest control of his life back from an urban predator. The lyrics are hissed in a raspy Dirty Harry voice, with myriad ghoulish vocals swooping through the mix like bats, with High Noon urgency.

“Iceman” is a gospel-tinged nursery-rhyme dirge about a family man who is trapped in a mountain snowstorm while out exploring, and is packed in a block of ice for 10,000 years. It is either the story of “Otzi the Iceman,” who was discovered in the Alps in 1991, or a cautionary tale about crawling within ourselves as artists only to alienate those around us. Is it a savvy self-conscious lesson in taking the moment for granted, while obsessed with future developments, like waiting for Bowie?

The lineup on The Pandemic Symphony is practically a roster of Portland’s rock elite: King Black Acid leader Riddle, Eric Matthews (Cardinal), Thee Slayer Hippy (Poison Idea, Obscured By Clouds), Kevin Cozad (Neros Rome, Obscured By Clouds), and Tony Lash, plus Angell’s wife, daughter, and brother Theo Angell, a brilliant, Brooklyn-based musician/filmmaker. The record’s intricate production and top-flight musicianship make it sound expensive, but the richly layered psych-pop sound was achieved on a tight budget. Pandemic is an innovative pastiche of vocal layering, pianos, and alien guitar effects that can be both darkly cinematic and dance-able; the intoxicating atmosphere that radiates throughout gives this “solo” project a full band feel.

Attempting to describe Angell’s debut album Private Player, the New Yorker compared it to the band Love’s psychedelic masterpiece, Forever Changes. Although clearly a compliment, that is perhaps missing the mark. The guitar on Angell’s records is there to support the piano, so his music feels more confessional than Arthur Lee’s. On The Pandemic Symphony the ballad “The Cost of Art,” with only his piano behind him, Angell addresses Portland’s polarizing transplant, Everclear leader Art Alexakis, who enjoyed a fast rise and harder fall. Angell calls him out for moving in and then mistreating the locals on his way to success before losing it all in the end. But he also exposes his maturity as a songwriter by acknowledging the irony of his criticizing the fallen star without having reached that level himself. There is understandable heartache but no bitterness in Angell’s work. On The Pandemic Symphony there are hints of James Blake and early ’70s Bowie, with dashes of Leonard Cohen and Prince, yet with his own musical vocabulary Angell remains dreamy, defiant, sexy, and elusive. With or without major-label support, Angell’s canon is an ever-evolving cabinet of curiosities, and if he hears the new record, David Bowie is certain to interrupt another breakfast with a phone call.

Editor's Note:

After this article was published, we heard from longtime David Bowie producer/bandmate/friend Tony Visconti, and it seems that something was lost in translation in our chat with Joe Hurley regarding Mr. Bowie's health status. We regret the miscommunication and apologize to Tony and David for jumping to conclusions based on Mr. Bowie's low-key industry presence these last few years. Tony was kind enough to share this firsthand update on his longtime friend's current state:

"In the past few years I have met up with Bowie for lunch, as old friends do. Oddly enough, I saw David yesterday and he looked, sounded, and laughed like a healthy man. He's rosy-cheeked, in excellent health, and full of sharp, witty humor. He is in SERIOUSLY GOOD SHAPE. He is in fine fettle and I am certain the world hasn't heard the last of him."

Needless to say, we're thrilled to hear it.

—Dave Mandl

Brooklynrail.org